Let’s [Snap]Chat! The Use of Digital Media in Archaeology

by cook_kTechnology, Social Media, Archaeology, Public Archaeology, EnglishContributed by Stephanie Halmhofer (MA Student, University of Toronto)

How many of us start our day off by logging into some sort of digital media site and scrolling through its posts? According to recent stats, millions of us. Many archaeologists are starting to jump on the digital media bandwagon through sites such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and online blogs. The archaeology department at the University of York, for example, even has a website dedicated to the use of digital media for their students and faculty. Some archaeologists, however, are still resistant to the idea. There are certainly some seemingly strange uses of digital media out there that could add to the resistance. Just this morning I read a news article about a new app which will allow users to record messages (vocal and written) to be released after death to their loved ones via whichever digital media platform they have chosen. Those who have not yet embraced the digital media world are sure to raise an eyebrow at an application like that. I’ll admit that even I did, and I’ve plastered myself all over digital media.

Nevertheless, digital media has amazing prospects for the field of archaeology. Archaeologists are experimental people by nature, whether it be at attempting flint-knapping and ceramic production, or simply trying out a new beer. So why shouldn’t we experiment with digital media? Let’s take a look at some of the ways it can benefit us.

1) Digital media opens up communication. Communication is one of the most important aspects of archaeology. We need to be able to effectively communicate our research to those within and outside of the field. We can’t deny that digital media is an incredible communication tool. Take a look at the stats for Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram (courtesy of www.statista.com). By the end of 2016, Facebook had roughly 1.79 billion monthly active users, Twitter has 317 million monthly active users, and Instagram had 600 million monthly active users. Sure, your Tweet or Instragram photo won’t instantly be sent to every single one of those people. But through including a simple hashtag (which are used on all digital media sites), such as #archaeology or, one of my favourites, #canadianarchaeology, users with similar interests can search those hashtags and see your posts. Even conferences are jumping on the hashtag bandwagon. During the Archaeological Institute of American’s recent conference in Toronto, #AIAToronto and #AIASCS popped up on Twitter before the conference had even started, linking not only visitors at the conference but those who couldn’t make it in person. The Society for American Anthropololgy’s upcoming 2017 conference in Vancouver already has a hashtag, #SAA2017, as does the Canadian Archaeological Association for their 2017 Conference in Ottawa (#CAA2017). Dr. Lorna Richardson, a Post-Doc at Umeå University in Sweden, is taking this one step further by proposing the first ever Public Archaeology Twitter Conference . Through use of #PATC1, authors will present their papers and answer questions, just like any conference, only this time through the use of 6-12 Tweets (plus additional Tweets for questions). Unlike other in-person conferences, however, this conference will have the ability to engage hundreds, thousands, or even millions more researchers, students, or people with a general interest in archaeology who would otherwise be unable to attend an in-person conference (where often the cost of attending is a major detriment).

2) Promoting and highlighting current research and events. This keeps building on the idea of communication, especially when used in ways such as what Dr. Richardson has proposed with PATC1. Including a hashtag, such as #archaeology, #canadianarchaeology, #glassbeads, etc. with a link to your recent research, project, or a conference will essentially guarantee that your work will reach everyone who is interested in the topic. And through the ability to “retweet” or “share”, those users can continue to share your research with millions more. Just this morning, for example, I logged into Facebook from my desk in Toronto and saw that my blog had been shared by the Saskatchewan Archaeological Society on their Facebook page. Taking a look at my blog stats right after that, I saw that 30 people had visited my site since the SAS had made their post. Furthermore, these 30 people were visiting not just from Canada, they were also from France and the USA. I hadn’t written any new blog posts within that 24-hour time period, so I think it’s safe to say that my sudden influx of 30 readers was thanks to the SAS.

The post from the Saskatchewan Archaeological Society and the effects it had on my blog the following day

It’s not just fellow archaeological colleagues to whom we want to promote our research and events. Digital media is a fantastic way for people outside of archaeology to become involved by following the posts made by archaeologists. Nicolás Laracuente describes the use of digital media as a new form of public archaeology where archaeologists can better engage with free-choice learners, or those who learn through following their individual interests. In this case, they learn by following the posts made by archaeologists or archaeological organizations, and through short-term online engagements.

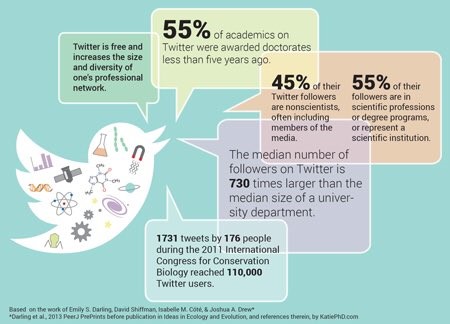

3) Build and engage with the archaeological community. This is especially important for students and early-career archaeologists, like myself. Take a look at this image from the American Scientist blog, which has been circulating through the Twittersphere as of late.

While it focuses on the sciences as a whole, this image really illustrates the amazing potential Twitter holds to help us connect archaeologists with each other and with non-archaeologists, and how we can build newer and bigger networks. As undergraduate and graduate students, and early-career archaeologists, networking can be a daunting task. We don’t always have the opportunities or capabilities to attend conferences, which used to be prime networking locations. We’ve also been raised in a digital world with increasing reliance on all forms of technology. For my generation, the new generation of archaeologists, digital media is our new networking tool. It’s where we can meet and connect with archaeologists from all around the world. It’s where we can find graduate study opportunities. It’s where we can find job postings and learn from the experiences of others who choose to share job experiences online. And it’s where we can share our own research and learn from the research of others. For example, my current research has been focused on a very rare type of glass bead. So rare, in fact, that I had a hard time getting started with my research. Luckily I was very quickly informed of an online chat forum about glass beads for archaeologists, historians, and those with general interests. One descriptive post later I had enough leads to keep me busy for four months. I now have new information I can share with the community from where these beads were found, a significant chunk of my graduate research completed, my presentation ready for the CAA 2017 conference, and a future publication in the works. All thanks to a single post in an online chat forum.

So there you have it. With hundreds of millions of people around the world logging into various digital media platforms every single month, this provides archaeologists with an amazing opportunity to dramatically open up our communication lines. We can connect with other archaeologists, future archaeologists, and those with general interests in archaeology. We can promote our research, look for help with our research, and engage with people we might not otherwise have an opportunity to engage with. It used to be said that if you can’t explain your research to a five-year-old child, do you really understand your research at all? In today’s age of digital media, perhaps the better question is that if you can’t explain your research in 140 characters or less, do you really understand your research at all?

Add new comment